Intelligent Stretching Part 1

by Paul Chek

Stretching is an ancient form of exercise that goes deeper into evolution than man himself. If you’re wondering what I mean, watch any cat or dog and you will often see them stretch after they have arisen from a rest. Even birds can often be seen stretching their wing muscles too.

Stretching is an ancient form of exercise that goes deeper into evolution than man himself. If you’re wondering what I mean, watch any cat or dog and you will often see them stretch after they have arisen from a rest. Even birds can often be seen stretching their wing muscles too.

Most ancient martial arts and conditioning systems incorporate stretching as an integral part of athletic development. Stretching has also been part of healing practices for thousands of years.

But have we learned anything recently that will improve your results with stretching? Yes, we have. In this multi-part article, I’ll share these tips for getting maximum results in minimum time with stretching:

- Learning about tonic, phasic and mixed muscle types and which ones should be stretched first.

- Discovering when is the best time to stretch based on the desired outcome.

- Reviewing two basic approaches for lengthening the muscle-tendon unit and determining which one is best for you.

- Changing your stretching routine as your body or your activities change, if you want the best results!

Not all muscles are alike

You’ve likely heard of the postural muscles, ones that are ideally suited to hold you up against gravity. Often, people use the term “tonic muscles” interchangeably with “postural muscles.” In reality, however, the tonic muscles and postural muscles are different.

While postural muscles do hold you up against gravity, for the most part, they are the muscles on the back of your body called extensor muscles. Gravity is always trying to push you into the fetal position so the postural muscles primarily resist motion in that direction.

On the other hand, tonic muscles are ones that react to faulty loading by shortening, tightening and becoming more easily facilitated. This means they become workaholics very easily and suffer the typical soft tissue stress that goes with doing more than a muscle should!

Before moving forward, let’s clarify the term faulty loading. For this article, it means any overuse, underuse, abuse (such as trauma) or disuse (such as not getting adequate exercise).

Tonic muscles also have a lower threshold of stimulation than other skeletal muscles because they’re composed of at least 51 percent slow-twitch muscle fibers that have a greater capacity for prolonged work, such as aerobic activity or holding you up against gravity.

Vladimir Janda, a pioneer who identified some of the tonic and phasic muscles, also discovered that these muscles tend to shorten and tighten in hospital patients exposed to prolonged bed rest (like those in a coma) and need to be regularly stretched out by physical therapists to avoid future problems with joints and connective tissues.

Conversely, phasic muscles contain at least 51 percent fast-twitch muscle fibers (explosive) and they react to faulty loading by lengthening and weakening (relative to their functional antagonists or opposing muscles).

This can be quite a problem since the same event that causes a tonic muscle to shorten and tighten usually results in the lengthening and relative weakening of any opposing phasic muscle(s). This results in a condition referred to as a muscle imbalance among those in the field of sports conditioning and musculoskeletal rehabilitation.

Mixed muscles are a third classification, identified by the fact that they show no preference to length or strength changes in response to faulty loading (but not including typical fatigue). For example, your deepest abdominal muscles, the transverse abdominis (TVA) and your diaphragm, are mixed muscles.

The problem of muscle balance

The action of tonic and phasic muscles can create quite a problem in the body because, in many instances, both muscle groups are directly opposed and/or opposed in their postural actions on various joints in the body.

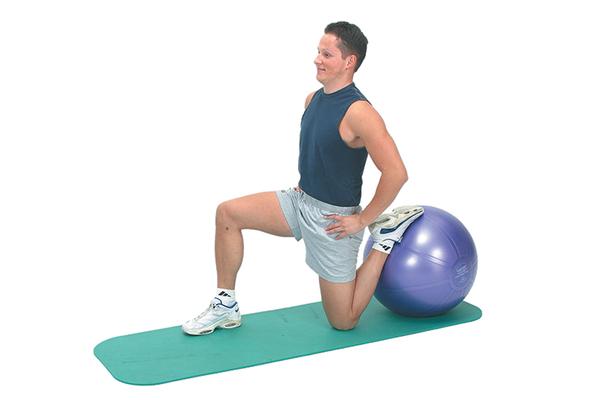

See how this works in Figure 1. As the tonic hip flexor muscles (in red) shorten and tighten, the phasic abdominal and hamstring muscles are strung tautly and become longer.

Over time, the tonic muscles physically or structurally shorten, while the stretch stimulus created by a shortened tonic muscle will lead to structural lengthening of a phasic antagonist. This perpetually destabilizes joint structures throughout the entire body, being most problematic locally (the site where the imbalance began) in most cases.

In the table accompanying this article, you’ll see a list of commonly recognized tonic and phasic muscles in the body. In short order, you’ll notice that many tonic muscles (such as the pectoralis minor) have phasic antagonists (such as the middle trapezius and rhomboids).

With this knowledge, you’ll have a better idea why general stretching rarely improves overall musculoskeletal performance, or provides the kind of injury prevention that a more skillful application of stretching will protect.

Muscles and their connective tissues act like springs, creating tension and force on a joint complex even at rest. If a muscle becomes lengthened or shortened relative to its antagonist, it is much like having some tight strings and some loose strings on your guitar or piano. Neither instrument is capable of playing good music!

So, if you show up to a tennis match and merely stretch all of your muscles, will you be balancing the system for improved joint stability, injury prevention and improved performance? You’ll do no more good than if you loosen or tighten all the strings of an out-of-tune musical instrument.

To stretch more effectively requires that you test each of the tonic muscles to determine which of them are shortened and in need of balancing. This will automatically improve the function and balance of a phasic antagonist.

Unfortunately, describing all of the necessary tests you’ll need to do is beyond the scope of this article. If you are interested in accurately assessing your muscle balance, I recommend studying my book, The Golf Biomechanic’s Manual.

On the other hand, if you want a less technical but effective method for identifying which muscles to stretch so you can balance your body before any work or exercise activity, or just to improve energy flow in your body, you’ll want to consider reading How To Eat, Move and Be Healthy!

In the latter book, I show you how to execute the 20 most commonly used stretches in the form of a test. Having completed these tests, you’ll proceed to stretch the short, tight muscles, so you can balance your body like you would tune a violin or piano.

Although I recommend these books for the wealth of practical information in them, you can also balance your body by simply trying any and all the stretches you know and sticking to this guideline: If it’s not tight, DON’T STRETCH IT!

Failing to follow this simple idea will result in one of two responses:

- If you complete a typical general stretching routine, you will simply be loose and out of balance.

- Choosing not to stretch an out-of-balance body and simply exercising results in a progressively tighter, potentially brittle out-of-balance body.

Neither choice is optimal for your health or performance!

In part 2, I’ll explain when is the best time for you to stretch your muscles, what is the best way to stretch them and how long you should maintain a good stretch.

Love and chi,

Paul

Chart references

- Spring, Hans, et. Al, Stretching and Strengthening Exercises, New York, NY, Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc., 1991.

- Lewit, Karel, Manipulative Therapy in Rehabilitation of the Locomotor System, 3rd Edition, Great Britain, Butterworth-Heinemann, Reed Educational and Professional Publishing Ltd, 1999.